- Home

- Hesse, Karen

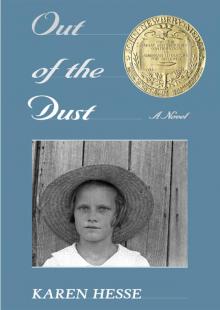

Out of the Dust (9780545517126) Page 5

Out of the Dust (9780545517126) Read online

Page 5

And later,

when the clouds lift,

the farmers, surveying their fields,

nod their heads as

the frail stalks revive,

everyone, everything, grateful for this moment,

free of the

weight of dust.

January 1935

Haydon P. Nye

Haydon P. Nye died this week.

I knew him to wave,

he liked the way I played piano.

The newspaper said when Haydon first came

he could see only grass,

grass and wild horses and wolves roaming.

Then folks moved in and sod got busted

and bushels of wheat turned the plains to gold,

and Haydon P. Nye

grabbed the Oklahoma Panhandle in his fist

and held on.

By the time the railroad came in

on land Haydon sold them,

the buffalo and the wild horses had gone.

Some years

Haydon Nye saw the sun dry up his crop,

saw the grasshoppers chew it down,

but then came years of rain

and the wheat thrived,

and his pockets filled,

and his big laugh came easy.

They buried Haydon Nye on his land,

busted more sod to lay down his bones.

Will they sow wheat on his grave,

where the buffalo

once grazed?

January 1935

Scrubbing Up Dust

Walking past the Crystal Hotel

I saw Jim Martin down on his knees.

He was scraping up mud that had

dried to crust

after the rain mixed with dust Sunday last.

When I got home

I took a good look at the steps

and the porch and the windows.

I saw them with Ma’s eyes and thought about

how she’d been haunting me.

I thought about Ma,

who would’ve washed clothes,

beaten furniture,

aired rugs,

scrubbed floors,

down on her knees,

brush in hand,

breaking that mud

like the farmers break sod,

always watching over her shoulder

for the next duster to roll in.

My stubborn ma,

she’d be doing it all

with my brother Franklin to tend to.

She never could stand a mess.

My father doesn’t notice the dried mud.

Least he never tells me,

not that he tells me much of anything these days.

With Ma gone,

if the mud’s to be busted,

the job falls to me.

It isn’t the work I hate,

the knuckle-breaking work of beating mud out of

every blessed thing,

but every day

my fingers and hands

ache so bad. I think

I should just let them rest,

let the dust rest,

let the world rest.

But I can’t leave it rest,

on account of Ma,

haunting.

January 1935

Outlined by Dust

My father stares at me

while I sit across from him at the table,

while I wash dishes in the basin,

my back to him,

the picked and festered bits of my hands in agony.

He stares at me

as I empty the wash water at the roots

of Ma’s apple trees.

He spends long days

digging for the electric-train folks

when they can use him,

or working here,

nursing along the wheat,

what there is of it,

or digging the pond.

He sings sometimes under his breath,

even now,

even after so much sorrow.

He sings a man’s song,

deep with what has happened to us.

It doesn’t swing lightly

the way Ma’s voice did,

the way Miss Freeland’s voice does,

the way Mad Dog sings.

My father’s voice starts and stops,

like a car short of gas,

like an engine choked with dust,

but then he clears his throat

and the song starts up again.

He rubs his eyes

the way I do,

with his palms out.

Ma never did that.

And he wipes the milk from his

upper lip same as me,

with his thumb and forefinger.

Ma never did that, either.

We don’t talk much.

My father never was a talker.

Ma’s dying hasn’t changed that.

I guess he gets the sound out of him with the

songs he sings.

I can’t help thinking

how it is for him,

without Ma.

Waking up alone, only

his shape

left in the bed,

outlined by dust.

He always smelled a little like her

first thing in the morning,

when he left her in bed

and went out to do the milking.

She’d scuff into the kitchen a few minutes later,

bleary eyed,

to start breakfast.

I don’t think she was ever

really meant for farm life,

I think once she had bigger dreams,

but she made herself over

to fit my father.

Now he smells of dust

and coffee,

tobacco and cows.

None of the musky woman smell left that was Ma.

He stares at me,

maybe he is looking for Ma.

He won’t find her.

I look like him,

I stand like him,

I walk across the kitchen floor

with that long-legged walk

of his.

I can’t make myself over the way Ma did.

And yet, if I could look in the mirror and see her in

my face.

If I could somehow know that Ma

and baby Franklin

lived on in me …

But it can’t be.

I’m my father’s daughter.

January 1935

The President’s Ball

All across the land,

couples dancing,

arm in arm, hand in hand,

at the Birthday Ball.

My father puts on his best overalls,

I wear my Sunday dress,

the one with the white collar,

and we walk to town

to the Legion Hall

and join the dance. Our feet flying,

me and my father,

on the wooden floor whirling

to Arley Wanderdale and the Black Mesa Boys.

Till ten,

when Arley stands up from the piano,

to announce we raised thirty-three dollars

for infantile paralysis,

a little better than last year.

And I remember last year,

when Ma was alive and we were

crazy excited about the baby coming.

And I played at this same party for Franklin D.

Roosevelt

and Joyce City

and Arley.

Tonight, for a little while

in the bright hall folks were almost free,

almost free of dust,

almost free of debt,

almost free of fields of withered wheat.

Most of the night I think I smiled.

And twice my father laughed.

Imagine.<

br />

January 1935

Lunch

No one’s going hungry at school today.

The government

sent canned meat,

rice,

potatoes.

The bakery

sent loaves of bread,

and

Scotty Moore, George Nall, and Willie Harkins

brought in milk,

fresh creamy milk

straight from their farms.

Real lunch and then

stomachs

full and feeling fine

for classes

in the afternoon.

The little ones drank themselves into white

mustaches,

they ate

and ate,

until pushing back from their desks,

their stomachs round,

they swore they’d never eat again.

The older girls,

Elizabeth and LoRaine, helped Miss Freeland

cook,

and Hillary and I,

we served and washed,

our ears ringing with the sound of satisfied children.

February 1935

Guests

In our classroom this morning,

we came in to find a family no one knew.

They were shy,

a little frightened,

embarrassed.

A man and his wife, pretty far along with a baby

coming,

a baby

coming

two little kids

and a grandma.

They’d moved into our classroom during the night.

An iron bed

and some pasteboard boxes. That’s all they had.

They’d cleaned the room first, and arranged it,

making a private place for themselves.

“I’m on the look for a job,” the man said.

“The dust blew so mean last night

I thought to shelter my family here awhile.”

The two little kids turned their big eyes

from Miss Freeland

back to their father.

“I can’t have my wife sleeping in the cold truck,

not now. Not with the baby coming so soon.”

Miss Freeland said they could stay

as long as they wanted.

February 1935

Family School

Every day we bring fixings for soup

and put a big pot on to simmer.

We share it at lunch with our guests,

the family of migrants who have moved out from dust

and Depression

and moved into our classroom.

We are careful to take only so much to eat,

making sure there’s enough soup left in the pot for

their supper.

Some of us bring in toys

and clothes for the children.

I found a few things of my brother’s

and brought them to school,

little feed-sack nighties,

so small,

so full of hope.

Franklin

never wore a one of the nighties Ma made him,

except the one we buried him in.

The man, Buddy Williams,

helps out around the school,

fixing windows and doors,

and the bad spot on the steps,

cleaning up the school yard

so it never looked so good.

The grandma takes care of the children,

bringing them out when the dust isn’t blowing,

letting them chase tumbleweeds across the field

behind the school,

but when the dust blows,

the family sits in their little apartment inside our

classroom,

studying Miss Freeland’s lessons

right alongside us.

February 1935

Birth

One morning when I arrive at school

Miss Freeland says to keep the kids out,

that the baby is coming

and no one can enter the building

until the birthing is done.

I think about Ma

and how that birth went.

I keep the kids out and listen behind me,

praying for the sound of a baby

crying into this world,

and not the silence

my brother brought with him.

And then the cry comes

and I have to go away for a little while

and just walk off the feelings.

Miss Freeland rings the bell to call us in

but I’m not ready to come back yet.

When I do come,

I study how fine that baby girl is. How perfect,

and that she is wearing a feed-sack nightgown that

was my brother’s.

February 1935

Time to Go

They left a couple weeks after the baby came,

all of them crammed inside that rusty old truck.

I ran half a mile in their dust to catch them.

I didn’t want to let that baby go.

“Wait for me,” I cried,

choking on the cloud that rose behind them.

But they didn’t hear me.

They were heading west.

And no one was looking back.

February 1935

Something Sweet from Moonshine

Ashby Durwin

and his pal Rush

had themselves a

fine operation on the Cimarron River,

where the water still runs a little,

though the fish are mostly dead

from the dust floating on the surface.

Ashby and Rush were cooking up moonshine

in their giant metal still on the bank

when Sheriff Robertson caught them.

He found jugs of finished whiskey,

and barrels and barrels of mash,

he found two sacks of rye,

and he found sugar,

one thousand pounds of sugar.

The government men took Ashby and Rush off to

Enid

for breaking the law,

but Sheriff Robertson stayed behind,

took apart the still,

washed away the whiskey and the mash,

and thought about that sugar,

all that sugar, one-half ton of sugar.

Sheriff decided

some should find its way

into the mouths of us kids.

Bake for them, Miss Freeland, he said,

bake them cakes and cookies and pies,

cook them custard and cobbler and crisp,

make them candy and taffy and apple pandowdy.

Apple pandowdy!

These kids,

Sheriff Robertson said,

ought to have something sweet to

wash down their dusty milk.

And so we did.

February 1935

Dreams

Each day after class lets out,

each morning before it begins,

I sit at the school piano

and make my hands work.

In spite of the pain,

in spite of the stiffness

and scars.

I make my hands play piano.

I have practiced my best piece over and over

till my arms throb,

because Thursday night

the Palace Theatre is having a contest.

Any man, woman, or child

who sings,

dances,

reads,

or plays worth a lick

can climb onto that stage.

Just register by four P.M.

and give them a taste of what you can do

and you’re in,

performing for the crowd,

warming up the audience for the

Hazel Hurd Players.

I figure if I practice enough

I won’t shame myself.

And we sure could use the extra cash

if I won.

Three-dollar first prize,

two-dollar second,

one-dollar third.

But I don’t know if I could win anything,

not anymore.

It’s the playing I want most,

the proving I can still do it.

without Arley making excuses.

I have a hunger,

for more than food.

I have a hunger

bigger than Joyce City.

I want tongues to tie, and

eyes to shine at me

like they do at Mad Dog Craddock.

Course they never will,

not with my hands all scarred up,

looking like the earth itself,

all parched and rough and cracking,

but if I played right enough,

maybe they would see past my hands.

Maybe they could feel at ease with me again,

and maybe then,

I could feel at ease with myself.

February 1935

The Competition

I suppose everyone in Joyce City and beyond,

all the way to Felt

and Keyes

and even Guymon,

came to watch the talent show at the Palace,

Thursday night.

Backstage,

we were seventeen amateur acts,

our wild hearts pounding,

our lips sticking to our teeth,

our urge to empty ourselves

top and bottom,

made a sorry sight

in front of the

famous Hazel Hurd Players.

But they were kind to us,

helped us with our makeup and our hair,

showed us where to stand,

how to bow,

and the quickest route to the

toilet.

The audience hummed on the other side of the

closed curtain,

Ivy Huxford

kept peeking out and giving reports

of who was there,

and how she never saw so many seats

filled in the Palace,

and that she didn’t think they could

squeeze a

rattlesnake

into the back

even if he paid full price,

the place was so packed.

My father told me he’d come

once chores were done.

I guess he did.

The Grover boys led us off.

They worked a charm,

Baby on the sax,

Jake on the banjo,

and Ben on the clarinet.

The Baker family followed, playing

just like they do at home

every night after dinner.

They didn’t look nervous at all.

Out of the Dust (9780545517126)

Out of the Dust (9780545517126)