- Home

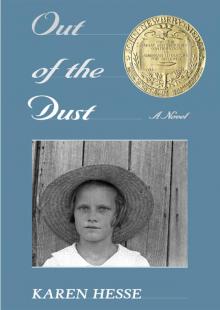

- Hesse, Karen

Out of the Dust (9780545517126) Page 3

Out of the Dust (9780545517126) Read online

Page 3

Mr. Chaffin, Mr. Haverstick, and Mr. French,

they’ve delivered their harvest too,

dropping it at the Joyce City grain elevator.

Daddy asked Mr. Haverstick how things looked

and Mr. Haverstick said he figures

he took eight bushels off a twenty-bushel acre.

If Daddy gets five bushels to his acre

it’ll be a miracle.

June 1934

On the Road with Arley

Here’s the way I figure it.

My place in the world is at the piano.

I’m earning a little money playing,

thanks to Arley Wanderdale.

He and his Black Mesa Boys have connections in

Keyes and Goodwell and Texhoma.

And every little crowd

is grateful to hear a rag or two played

on the piano

by a long-legged, red-haired girl,

even when the piano has a few keys soured by dust.

At first Ma crossed her arms

against her chest

and stared me down,

hard-jawed and sharp, and said I couldn’t go.

But the money helped convince her,

and the compliment from Arley and his wife, Vera,

that they’d surely bring my ma along to play too,

if she wasn’t so far gone with a baby coming.

Ma said

okay,

but only for the summer,

and only if she didn’t hear me gripe how I was tired,

or see me dragging my back end around,

or have to call me twice upon a morning,

or find my farm chores falling down,

and only if Arley’s wife, Vera, kept an eye on me.

Arley says my piano playing is good.

I play a set of songs with the word baby in the title,

like “My Baby Just Cares for Me”

and “Walking My Baby Back Home.”

I picked those songs on purpose for Ma,

and the folks that come to hear Arley’s band,

they like them fine.

Arley pays in dimes.

Ma’s putting my earnings away I don’t know where,

saving it to send me to school in a few years.

The money doesn’t matter much to me.

I’d play for nothing.

When I’m with Arley’s boys we forget the dust.

We are flying down the road in Arley’s car,

singing,

laying our voices on top of the

beat Miller Rice plays on the back of Arley’s seat,

and sometimes, Vera, up front, chirps crazy notes

with no words

and the sounds she makes seem just about amazing.

It’s being part of all that,

being part of Arley’s crowd I like so much,

being on the road,

being somewhere new and interesting.

We have a fine time.

And they let me play piano, too.

June 1934

Hope in a Drizzle

Quarter inch of rain

is nothing to complain about.

It’ll help the plants above ground,

and start the new seeds growing.

That quarter inch of rain did wonders for Ma, too,

who is ripe as a melon these days.

She has nothing to say to anyone anymore,

except how she aches for rain,

at breakfast,

at dinner,

all day,

all night,

she aches for rain.

Today, she stood out in the drizzle

hidden from the road,

and from Daddy,

and she thought from me,

but I could see her from the barn,

she was bare as a pear,

raindrops

sliding down her skin,

leaving traces of mud on her face and her long back,

trickling dark and light paths,

slow tracks of wet dust down the bulge of her belly.

My dazzling ma, round and ripe and striped

like a melon.

July 1934

Dionne Quintuplets

While the dust blew

down our road,

against our house,

across our fields,

up in Canada

a lady named Elzire Dionne

gave birth to five baby girls

all at once.

I looked at Ma,

so pregnant with one baby.

“Can you imagine five?” I said.

Ma lowered herself into a chair.

Tears dropping on her tight stretched belly,

she wept

just to think of it.

July 1934

Wild Boy of the Road

A boy came by the house today,

he asked for food.

He couldn’t pay anything, but Ma set him down

and gave him biscuits

and milk.

He offered to work for his meal,

Ma sent him out to see Daddy.

The boy and Daddy came back late in the afternoon.

The boy walked two steps behind,

in Daddy’s dust.

He wasn’t more than sixteen.

Thin as a fence rail.

I wondered what

Livie Killian’s brother looked like now.

I wondered about Livie herself.

Daddy asked if the boy wanted a bath,

a haircut,

a change of clothes before he moved on.

The boy nodded.

I never heard him say more than “Yes, sir” or

“No, sir” or

“Much obliged.”

We watched him walk away

down the road,

in a pair of Daddy’s mended overalls,

his legs like willow limbs,

his arms like reeds.

Ma rested her hands on her heavy stomach,

Daddy rested his chin on the top of my head.

“His mother is worrying about him,” Ma said.

“His mother is wishing her boy would come home.”

Lots of mothers wishing that these days,

while their sons walk to California,

where rain comes,

and the color green doesn’t seem like such a miracle,

and hope rises daily, like sap in a stem.

And I think, some day I’m going to walk there too,

through New Mexico and Arizona and Nevada.

Some day I’ll leave behind the wind, and the dust

and walk my way West

and make myself to home in that distant place

of green vines and promise.

July 1934

The Accident

I got

burned

bad.

Daddy

put a pail of kerosene

next to the stove

and Ma,

fixing breakfast,

thinking the pail was

filled with water,

lifted it,

to make Daddy’s coffee,

poured it,

but instead of making coffee,

Ma made a rope of fire.

It rose up from the stove

to the pail

and the kerosene burst

into flames.

Ma ran across the kitchen,

out the porch door,

screaming for Daddy.

I tore after her,

then,

thinking of the burning pail

left behind in the bone-dry kitchen,

I flew back and grabbed it,

throwing it out the door.

I didn’t know.

I didn’t know Ma was coming back.

The flaming oil

splashed

onto her apron,

&

nbsp; and Ma,

suddenly Ma,

was a column of fire.

I pushed her to the ground,

desperate to save her,

desperate to save the baby, I

tried,

beating out the flames with my hands.

I did the best I could.

But it was no good.

Ma

got

burned

bad.

July 1934

Burns

At first I felt no pain,

only heat.

I thought I might be swallowed by the heat,

like the witch in “Hansel and Gretel,”

and nothing would be left of me.

Someone brought Doc Rice.

He tended Ma first,

then came to me.

The doctor cut away the skin on my hands, it hung in

crested strips.

He cut my skin away with scissors,

then poked my hands with pins to see what I could

feel.

He bathed my burns in antiseptic.

Only then the pain came.

July 1934

Nightmare

I am awake now,

still shaking from my dream:

I was coming home

through a howling dust storm,

my lowered face was scrubbed raw by dirt and wind.

Grit scratched my eyes,

it crunched between my teeth.

Sand chafed inside my clothes,

against my skin.

Dust crept inside my ears, up my nose,

down my throat.

I shuddered, nasty with dust.

In the house,

dust blew through the cracks in the walls,

it covered the floorboards and

heaped against the doors.

It floated in the air, everywhere.

I didn’t care about anyone, anything, only the piano. I

searched for it,

found it under a mound of dust.

I was angry at Ma for letting in the dust.

I cleaned off the keys

but when I played,

a tortured sound came from the piano,

like someone shrieking.

I hit the keys with my fist, and the piano broke into

a hundred pieces.

Daddy called to me. He asked me to bring water,

Ma was thirsty.

I brought up a pail of fire and Ma drank it. She had

given birth to a baby of flames. The baby

burned at her side.

I ran away. To the Eatons’ farm.

The house had been tractored out,

tipped off its foundation.

No one could live there.

Everywhere I looked were dunes of rippled dust.

The wind roared like fire.

The door to the house hung open and there was

dust inside

several feet deep.

And there was a piano.

The bench was gone, right through the floor.

The piano leaned toward me.

I stood and played.

The relief I felt to hear the sound of music after the

sound

of the piano at home.…

I dragged the Eatons’ piano through the dust

to our house,

but when I got it there I couldn’t play. I had swollen

lumps for hands,

they dripped a sickly pus,

they swung stupidly from my wrists,

they stung with pain.

When I woke up, the part

about my hands

was real.

July 1934

A Tent of Pain

Daddy

has made a tent out of the sheet over Ma

so nothing will touch her skin,

what skin she has left.

I can’t look at her,

I can’t recognize her.

She smells like scorched meat.

Her body groaning there,

it looks nothing like my ma.

It doesn’t even have a face.

Daddy brings her water,

and drips it inside the slit of her mouth

by squeezing a cloth.

She can’t open her eyes,

she cries out

when the baby moves inside her,

otherwise she moans,

day and night.

I wish the dust would plug my ears

so I couldn’t hear her.

July 1934

Drinking

Daddy found the money

Ma kept squirreled in the kitchen under the

threshold.

It wasn’t very much.

But it was enough for him to get good and drunk.

He went out last night.

While Ma moaned and begged for water.

He drank up the emergency money

until it was gone.

I tried to help her.

I couldn’t aim the dripping cloth into her mouth.

I couldn’t squeeze.

It hurt the blisters on my hands to try.

I only made it worse for Ma. She cried

for the pain of the water running into her sores,

she cried for the water that

would not soothe her throat

and quench her thirst,

and the whole time

my father was in Guymon,

drinking.

July 1934

Devoured

Doc sent me outside to get water.

The day was so hot,

the house was so hot.

As I came out the door,

I saw the cloud descending.

It whirred like a thousand engines.

It shifted shape as it came

settling first over Daddy’s wheat.

Grasshoppers,

eating tassles, leaves, stalks.

Then coming closer to the house,

eating Ma’s garden, the fence posts,

the laundry on the line, and then,

the grasshoppers came right over me,

descending on Ma’s apple trees.

I climbed into the trees,

opening scabs on my tender hands,

grasshoppers clinging to me.

I tried beating them away.

But the grasshoppers ate every leaf,

they ate every piece of fruit.

Nothing left but a couple apple cores,

hanging from Ma’s trees.

I couldn’t tell her,

couldn’t bring myself to say

her apples were gone.

I never had a chance.

Ma died that day

giving birth to my brother.

August 1934

Blame

My father’s sister came to fetch my brother,

even as Ma’s body cooled.

She came to bring my brother back to Lubbock

to raise as her own,

but my brother died before Aunt Ellis got here.

She wouldn’t even hold his little body.

She barely noticed me.

As soon as she found my brother dead,

she

had a talk with my father.

Then she turned around

and headed back to Lubbock.

The neighbor women came.

They wrapped my baby brother in a blanket

and placed him in Ma’s bandaged arms.

We buried them together

on the rise Ma loved,

the one she gazed at from the kitchen window,

the one that looks out over the

dried-up Beaver River.

Reverend Bingham led the service.

He talked about Ma,

but what he said made no sense

and I could tell

he didn’t truly know her,

he’d never even heard her play piano.

He asked my father

to name my baby brother.

My father, hunched over, said nothing.

I spoke up in my father’s silence.

I told the reverend

my brother’s name was Franklin.

Like our President.

The women talked as they

scrubbed death from our house.

I

stayed in my room

silent on the iron bed,

listening to their voices.

“Billie Jo threw the pail,”

they said. “An accident,”

they said.

Under their words a finger pointed.

They didn’t talk

about my father leaving kerosene by the stove.

They didn’t say a word about my father

drinking himself

into a stupor

while Ma writhed, begging for water.

They only said,

Billie Jo threw the pail of kerosene.

August 1934

Birthday

I walk to town.

I don’t look back over my shoulder

at the single grave

holding Ma and my little brother.

I am trying not to look back at anything.

Dust rises with each step,

there’s a greasy smell to the air.

On either side of the road are

the carcasses of jackrabbits, small birds, field mice,

stretching out into the distance.

My father stares out across his land,

empty but for a few withered stalks

like the tufts on an old man’s head.

I don’t know if he thinks more of Ma,

or the wheat that used to grow here.

There is barely a blade of grass

swaying in the stinging wind,

there are only these

lumps of flesh

that once were hands long enough to span octaves,

swinging at my sides.

I come up quiet

and sit behind Arley Wanderdale’s house,

where no one can see me, and lean my head back,

and close my eyes,

and listen to Arley play.

August 1934

Roots

President Roosevelt tells us to

plant trees. Trees will

break the wind. He says,

trees

will end the drought,

the animals can take shelter there,

children can take shelter.

Trees have roots, he says.

They hold on to the land.

That’s good advice, but

I’m not sure he understands the problem.

Trees have never been at home here.

They’re just not meant to be here.

Maybe none of us are meant to be here,

only the prairie grass

Out of the Dust (9780545517126)

Out of the Dust (9780545517126)